We would like to show you a description here but the site won’t allow us. Find free sheet music downloads - thousands of them, plus links to thousands of free sheet music sites, lessons, tips, and articles; many instrument, many musical styles.

Anthony Newman (born May 12, 1941) is an American classical musician. While mostly known as an organist, Newman is also a harpsichordist, pedal harpsichordist, pianist, fortepianist, composer, conductor, writer, and teacher. A specialist in music of the Baroque period, particularly the works of Johann Sebastian Bach, Newman considers himself to have played an important role in the movement towards historically informed performance. He has collaborated with noted musicians such as Kathleen Battle, Julius Baker, Itzhak Perlman, Eugenia Zukerman, Jean-Pierre Rampal, Leonard Bernstein, Michala Petri and Wynton Marsalis for whom he arranged and conducted In Gabriel’s Garden, the most popular classical record of 1996.[1]

Early life[edit]

Newman was born in Los Angeles, California. His father was a lawyer and his mother was a professional dancer and an amateur pianist. Newman started playing the piano by ear at age four and could read music before he could read words.[2] He was five when he first heard the music of J.S. Bach (the fifth Brandenburg Concerto)[3] and was 'delighted, elated and fascinated.'[4] At five he began piano lessons but decided to add organ after hearing his first Bach organ music (Toccata and Fugue in D minor). He had to wait until he was ten to begin organ lessons because before then his feet would not reach the pedals.[3] From the age of ten to seventeen he studied the organ with Richard Keys Biggs.[5]

At age seventeen Newman went to Paris, France, to study at l'École Normale de Musique. His primary teachers were Pierre Cochereau (organ), Madeleine de Valmalete (piano), and Marguerite Roesgen-Champion (harpsichord). He received a diplôme supérieur, with the commendations of the legendary pianist Alfred Cortot.[6]

Newman returned to the United States and received a B.S. in 1963 from the Mannes School of Music having studied organ with Edgar Hilliar, piano with Edith Oppens and composition with William Sydemann. He worked as a teaching fellow at Boston University while studying composition with Leon Kirchner at Harvard University. He received his M.A. in composition from Harvard in 1966 and his doctorate in organ from Boston University in 1967 where he studied organ with George Faxon and composition with Gardner Read and Luciano Berio for whom he also served as teaching assistant.[5]

Professional life[edit]

Newman's professional debut, in which he played Bach organ works on the pedal harpsichord, took place at the Carnegie Recital Hall in New York in 1967. Of this performance The New York Times wrote, 'His driving rhythms and formidable technical mastery...and intellectually cool understanding of the structures moved his audience to cheers at the endings.'[7] Based solely on the Times’ review, and without an audition, Columbia Records signed Newman to a recording contract. Clive Davis, head of Columbia Records, took his cue from the prevailing anti-establishment sentiment among young people and Newman's long hair and interest in Zen meditation and marketed Newman as a counterculture champion of Bach would could draw young audiences.[6] As a result, according to Newman, it took some years for him to 'live down' the image created by Davis and to be taken seriously in the classical music world.[8] But Newman did indeed draw young audiences as noted by Time magazine in a 1971 article in which they dubbed him the 'high priest of the harpsichord.'[9] After recording twelve albums for Columbia Records Newman left along with pianist André Watts, another of Davis' protégés, when Davis left Columbia in 1979.[10] Newman has gone on to make solo recordings for a variety of labels including Digitech, Excelsior, Helicon, Infinity Digital/Sony, Moss Music Group/Vox, Newport Classic, Second Hearing, Sheffield, Sine Qua Non, Sony, Deutsch Grammophon, and 903 Records.[5] Newman has recorded most of Bach's keyboard works on organ, harpsichord and piano as well as recording works of Scarlatti, Handel, and Couperin. On the fortepiano he has recorded the works of Beethoven and Mozart. As a conductor Newman has led international orchestras such as the Madeira Festival Orchestra, the Brandenburg Collegium, and the English Chamber Orchestra.[5]

For thirty years, starting in 1968, while Newman continued to record, concertize, compose, conduct and write, he taught music at The Juilliard School, Indiana University, and State University of New York at Purchase.[11]

Although initially intensely interested in composition, he became discouraged by the non-tonal music that was the focus of conservatory composition departments in the 1950s and '60s.[4][12] He returned to composition in the 1980s and developed a post-modern compositional style that took over from where pre-atonal post-modernism left off. He makes use of musical archetypes from the 17th, 18th, and 19th centuries as well as 20th century archetypes he has devised himself with the intent making new but accessible music.[13][14] Newman has written music for a range of instruments including organ, harpsichord, orchestra, guitar, violin, cello, flute chamber ensemble, piano, choral music and opera.[5] In 2011, Newman released a 20-CD set of his most important compositions on 903 Records.

Newman is music director of Bach Works and Bedford Chamber Concerts, and is on the board of Musical Quarterly magazine. He is also music director at St. Matthews Church, Bedford New York.

Baroque performance controversy[edit]

From the beginning Newman's interpretation of the music of J.S. Bach brought disdain from many musicians. His chosen tempos are generally extremely fast, and he often takes liberties with rhythm and ornamentation. Newman's argument in favor of his tempo is that what he calls the 'traditional' approach to Bach began 100 years after Bach's death and is misguided by a mystique and reverence for the composer that results in performances which are slow, rhythmically restrained and without the vivification of ornamentation.[6][15] In contrast, Newman's recordings of Bach have been considered 'exciting' by some who are skeptical of the validity of his interpretations.[16][17] In Newman's scholarly text, Bach and the Baroque, published in 1985 and revised in 1995, Newman supports his performance of Baroque music with a thorough analysis based on contemporary 17th and 18th century sources. Newman discusses how alterations to the written music - rhythmic variations such as rubato and notes inégales[18] as well as improvised ornamentation - were common in Bach's time and that fast movements were played faster than has been traditionally accepted. Scholarly opposition to Newman's approach was led by Frederick Neumann who had long-held that notes inégales were limited primarily to French performance practice and that Bach, who traveled relatively little, would not have been exposed to this technique.[19] In reviewing Newman's Bach and the Baroque in 1987 Neumann was at first somewhat gracious calling Newman '...a splendid keyboard performer who can dazzle his audiences with brilliant virtuosic feats. He can, and often does, play faster than perhaps any of his colleagues, and shows occasionally other signs of eccentricity.'[20] However he takes Newman to task for 'careless scholarship' citing misuse of terms such as tactus and misinterpretation of Bach's notation. But his strongest objection is to Newman's defense of the use of notes inégales in the performance of Bach. Most of Neumann's complaints question the validity of Newman's sources.[21]

Music critics too have been of two minds about Newman's interpretations of Bach, as illustrated in the following excerpts from The New York Times:

- 'A hiccup effect, or a sudden pause…is it rubato or something else that Mr. Newman applies…whatever it is, it lurches absurdly.'[22]

- 'His use of rubato as a structural device is particularly subtle – tiny pauses at various key spots to isolate and define vertical blocks within a phrase'[23]

- '…his accents…startle, even outrage…it is like listening to someone who speaks your native language with breathtaking fluency but in a thick accent, sprinkled with outrageous mispronunciations.'[24]

- 'His free use of rhythm to define larger phrase structures…does serve its purpose admirably in addition to adding a touch of drama to his performances.'[17]

Over time Newman's fast tempos have become relatively common in the performance of Bach's works[1] and his championing of the use of original instruments foreshadowed the historically informed performance movement in America by at least ten years.[25]

Personal life[edit]

At 28 Newman became a student of Zen Buddhism. He has practiced meditation several hours a day since then.[6] Newman was a volunteer at the hospice unit of Stamford Hospital from 1995 to 2004. He is married to Rabbi Mary Jane Newman. They have three sons.

Discography[edit]

Note: * indicates Newman's composition

903 Records

- J.S. Bach: Six Partitas

- J.S. Bach: Well Tempered Clavier Book 2, 1742

- J.S. Bach: Works for Pedal Harpsichord and Organ, 230

- J.S. Bach: Inventions in 2 Parts and Sinfonias in 3 Parts

- J.S. Bach: Great Works for Organ, 114

- The Music of J.S. Bach, 552

- J.S. Bach: French Suites, 30 Variations on Walsingham, 1722

- J.S. Bach: Six Partitas, 599

- J.S. Bach: English Suites, 1723

- My Favorite Bach Recordings, 2013

- J.S. Bach: Aria with 30 Variations

- Selections from Bach's Brandenburg Concerti

- J.S. Bach: Concerto in D Minor, Seven Toccatas for Harpsichord

- The Complete Collected Harpsichord Works of J.S. Bach

- The Complete Collected Organ Works of J.S. Bach

- Ad Nos, Ad Salutaremudam & Fantasia and Fugue on BACH, Music of Franz Liszt

- 3 Great Piano Duets

- Three Symphonies for Organ Solo *, 240

- Nicole and the Trial of the Century *, 1994

- Complete Works for Cello and Piano *, 121

- Complete Works for Violin and Piano *, 253

- Te Deum Laudamus *, 2007

- Large Chamber Works: Chamber Concerto, String Quartet #2, Piano Quintet *

- Complete Works for Organ *, 17501941, 2016

- American Classic Symphonies 1 and 2 *, 200

- Ittzes Plays Newman: Complete Works for Flute *, 309

- 12 Preludes and Fugues in Ascending Key Order for Piano Solo *

- Complete Music for Violin *, 112

- The Complete Original Works of Anthony Newman on 20 CDs *

- Concertino for Piano & Orchestra *

- On Fallen Heros: Orchestral Works *

- 6 Concertos *, 1915, 2015

- 9 Sonatas for Piano Solo *, 1331,

- 4 Symphonies *, 16851750, 2017

- Complete Works for Piano *, 10964, 2015

- Complete Chamber Works *, 1516

- Angel Oratorio *

- Complete Choral Works *, 2017

- Three Commissioned Works ^ 3-2015, 2015

- Lectures on Bach's Well Tempered Clavier, Books I and II, 1724, 2015

- Anthony Newman Plays Vierne, Mozart, Stravinsky, Newman, Bach, and Couperin

- Eugenia Zukerman and Anthony Newman play Bach, Haydn, and Hummel, 4143

- New Music for Heard and Mind *, 713

- Wedding Album, 170

- Wedding Album, Great Music for a Great Occasion

- Danielle Farina Plays Anthony Newman, 2013

- Complete Works for Piano Four Hands, 10814, 2016

- Great Works for the Organ Taken From Operas, 502

- Celebratory Music for Harpsichord, 215

Albany Records

- Absolute Joy, TROY 327, 1999

- Bach 2000 A Musical Tribute, 357, 2000

- Nicole and the Trial of the Century, 351, 20000

- Air Force Strings Label

- Newman: Concerto for Viola and Orchestra *

- Arabesque Recordings

- Newman's Valentine Songs, 2016

- Great Christmas Music for the Organ, Z6881, 2015

- Cambridge Records

- Music by Anthony Newman *, CRS B 2833, 1978

CBS Masterworks/Columbia

- Anthony Newman Harpsichord, M 30062,1968

- Anthony Newman – JS Bach, MS 7421, 1969

- Music for Organ, M 31127, 1969

- Anthony Newman Plays and Conducts Bach and Haydn, MQ 32300, 1973

- Anthony Newman Plays Harpsichord, Organ, and Pedal Harpsichord, M 32229, 1973

- Anthony Newman Plays J.S. Bach on the Pedal Harpsichord and Organ, MS 7309, 1968

- Bach: Goldberg Variations, M 30538, 1971

- The Well Tempered Clavier Book I, M2 32500, 1973

- The Well Tempered Clavier Book II, M2 32875, 1971

- Bach: The Six Brandenburg Concertos, M2 31398, 1972

- Lutheran Organ Mass, M2-32497, 1973

- Bhajebochstiannanas *, M 32439, 1973

- Organ Orgy, M 33268, 1975

- J.S. Bach/Anthony Newman, MS 7421, 1970

Connoisseur/Arabesque

- Brahms: The Two Cello Sonatas

- Mozart: Sonata in D for Two Fortepianos, 8125

Delos Productions

- Toning – Music for Healing and Energy *, DE 3213, 1997

- Music for a Sunday Morning, DE 3173, 1995

Deutsche Grammophon

- J.S. Bach: Arias, 429737, 1990

Digitech

- Handel: Water Music, Music for the Royal Fireworks, DIGI 103, 1979

Epiphany Records

- Concerts Royaux, EP-23, 2017

Essay

- Martin: Concerto for Seven Wind Instruments, 1014, 1991

Excelsior Records

- Masterpieces for Flute, 1982

- J.S. Bach: The Ultimate Organ Collection, EXL-2-5221, 1994

Helicon

- Bach at Lejansk, HE1010, 1996

- Bach In Celebration, 5107, 2000

- Bach: The Goldberg Variations

- Infinity Digital/Sony

- Bach Favorite Organ Works, QK 62385, 1992

- Bach: Goldberg Variations, QK 625882, 1996

- Bach: Toccatas, 1996

Kelos

- Bach: Great Works for Organ – Toccatas and Fugues, 2000

Khaeon

- Bach: The Well Tempered Clavier, Book 1 (complete piano and harpsichord) Vol I, KWM6001031, 2001

- Bach: The Well Tempered Clavier, Book 1 (complete piano and harpsichord) Vol II, KWM6001032, 2001

- Bach: The Well Tempered Clavier, Book 1 (complete piano and harpsichord) Vol III, KWM6001033, 2001

- Bach: The Great Works for the Organ

- Requiem *, KWM600102

Musical Heritage Society

- Telemann: Six “Konzerte” for Flute and Concertante Harpsichord, MHS 4523, 1982

- Two Generations: Concerti for Guitar and Chamber Orchestra, MHS 7397A, 1986

- Vivaldi Oboe Concerti, 513905X, 1993

Naxos

- The Four Seasons, 2006

Newport Classic

- Bach: Preludes and Fugues for Organ, Vol 1, NCD 60001, 1986

- Bach: Preludes and Fugues for Organ, Vol 2, NCD 60002, 1986

- Bach: Preludes and Fugues for Organ, Vol 3, NCD 60003, 1986

- Bach: Preludes and Fugues for Organ, Vol 4, NC 60004, 1986

- Bach: 6 Trio Sonatas, LC 8554, 1995

- Bach: Favorite Works for Organ, NCD 60090, 1992

- Bach Brandenburgs

- Beethoven: Four Great Sonatas (fortepiano), NCD 60040, 1988

- Beethoven: Violin Sonatas, NCD 60097, 1990

- Couperin: Two Organ Masses, NCD 60041, 1988

- Falla: Harpsichord Concerto, NC 60017, 1986

- Franck: Complete Works for the Organ, Vol I, NCD 60060, 1987

- Franck: Complete Works for the Organ, Vol I, NCD 60061, 1987

- J.S. Bach: Goldberg Variations, NCD 60024, 1987

- Bach: St. John Passion, NC 60015/1, 1986

- For God and Country, NCD 85533, 1994

- Keyboard Companion, NCD60026, 1991

- Cesar Frank; Complete Organ Works, Vol I, NCD060060, 1989

- Cesar Frank; Complete Organ Works, Vol II, NCD060061, 1989

- Mozart: 6 Fortepiano Sonatas, Vol I, NCD 60121, 1990

- Mozart: 4 Fortepiano Sonatas, Vol II, NCD 60122, 1990

- Mozart: 4 Fortepiano Sonatas, Vol III, NCD 60123, 1990

- Mozart: 4 Fortepiano Sonatas, Vol IV, NCD 60124, 1990

- W.A. Mozart: Seven Sonatas for Flute and Keyboard, NCD 60120, 1992

- Mozart: Complete Music for String Orchestra, NCD 60137, 1990

- Romantic Masterworks for Organ, Vol I, NCD 60060, 1989

- Romantic Masterworks for Organ, Vol II, NCD 60050, 1989

- Scarlatti Sonatas, NCD 60080, 1989

- Solo Organ Concerti, NCD 60071, 1989

- Beethoven: Piano Concerto No. 1 (fortepiano), NC 60031, 1987

- Beethoven: Piano Concertos No. 2 and 4 (fortepiano), NCD 60081, 1988

- Beethoven: Piano Concerto No. 3 (fortepiano), NC60007, 1986

- Beethoven: Piano Concerto No. 5 (fortepiano), NC 60027, 1987

- J.S. Bach: Concertos for One and Two Harpsichords, NC 60023, 1987

- Schumann: Piano Concerto, NCD 60034

- Beethoven: Violin Sonatas (fortepiano)

- Lutheran Organ Mass, NCD 60073

- On Fallen Heroes, Orchestral Works by Anthony Newman *, NCD 60140, 1992

- A Christman Album, NCD 60072, 1989

- Newman New Music *, NCD 60032, 1988

- Time Pieces, NCD 6044

- Contemporary American Piano Music, NCD 60048

OUR Recordings

- Telemann: Complete Recorder Sonatas, 8226909, 2014

Peter Pan

- Midnight in Havana, 4411, 1999

Sheffield

- A Bach Organ Recital, S-6, 1966

Sine Qua Non

- Bach: Favorite Organ Music, SQN-7771, 1976

- Bach: Organ Masterpieces, SA 2042, 1981

- Bach: Harpsichord Collection, SQN-2050

Sonoma

- Music for Organ, Brass, and Timpani, SAC-001, 2004

Sony

- Handel: Harpsichord Suites, SBK 62834, 1997, 1992

- Mozart: Famous Piano Sonatas, 63290, 1997

- Scarlatti: Harpsichord Sonatas, SBK 62654, 1989, 1996

- Baroque Duet, SK 46672, 1992

- Grace, 62035, 1995

- Saint-Saëns: Symphony No. 3, 'Organ', SK 53979, 1996

- Bach: The Brandenburg Concertos, 62472, 1994

- Classic Wynton, 60804, 1998

- In Gabriel's Garden, 66244, 1996

- Organ Orgy, 1974

- Bach: Goldberg Variations, SICC 2107, 1972

- Newman Plays Newman *, GS 9005, 1984

- The Wedding Album, MDK 47273, 1991

- Mozart: Eine Kleine Nachtmusik; Symphonies 35, 40, 41, 63272, 1997

- Lease Breakers, 1985

- Wynton Marsalis: The London Concert, 1995

Vox

- Bach: The Twenty-Four Organ Preludes and Fugues, Vol I, SVBX 5479, 1976

- Bach: The Twenty-Four Organ Preludes and Fugues, Vol II, SVBX 5480, 1976

- Bach: Toccatas for Harpsichord, 7520, 1996

- Famous Organ Works

- Bach: Suite No. 2 in B minor; Telemann: Suite in A minor, DVCL 9017, 1986

- Kodaly: Missa Brevis; Vaughan—Williams: Mass in G Minor, VCS 9076

- Vivaldi: Six Sonatas for Cello and Harpsichord, VCL 9074

Vivaldi Lived And Worked In

Vox Cum Laude

- J.S. Bach Six Sonatas for Flute and Keyboard, VCL 9070, 1984

- Bach: Well-Tempered Clavier, Book I, VCL 9056, 1983

- Bach: The 3 Gamba Sonatas, D-VCL 9020, 1983

- Jane's Hand: The Jane Auste Songbooks, VCL 7537, 1997

Vox Box

- JS Bach: 24 Preludes and Fugues Vol, I, CDX 5013, 1995

- JS Bach: 24 Preludes and Fugues, Vol. II, CDX 5100, 1995

MMG Vox Prima

- The Heroic Mr. Handel, MWCD 7100, 1986

Turnabout Vox

- Soler: 6 Concerti for 2 Keyboard Instruments, TV 341365, 1968

- Bach Organ Works, QTV-S 34656, 1976

- Organ Favorites for the Christmas Season, 34797,

- Bach at Madeira, 346656

Warner Classics

- The Bach Family, 61-7505, 1984

Awards[edit]

- 1958 French Government Bourse Scholarship

- 1963 Variell Fellowship, Harvard University

- 1964 Winner, International Composition Competition (organ solo), Nice, France

- 1967 Fulbright Fellowship

- 1977 Harpsichordist of the Year, Keyboard magazine

- 1978 Harpsichordist of the Year, Keyboard magazine

- 1981 Classical Keyboardist of the Year, Keyboard magazine

- 1986 Beethoven's Third Piano Concerto chosen Record of the Year by Stereo Review

- 1993 Boston University Distinguished Graduate award

- 2004 Musica Sacra award

- 30 consecutive annual composer awards from The American Society of Composers, Authors and Publishers (ASCAP)

References[edit]

- ^ abPolkow, Dennis, 'Anthony Newman Gets Some Respect', Calendar Archives, April, 1988.

- ^Garvey, Christine Newman, personal communication with Dean Farwood, June 20, 2010.

- ^ abNewman, Anthony, personal communication with Dean Farwood, May 15, 2010.

- ^ abArmstrong, Jon, Interview with Musician Anthony Newman.

- ^ abcdeDonahue, Thomas, Anthony Newman: Music, Energy, Spirit, Healing, 2001, Scarecrow Press, Inc., Lanham

- ^ abcdNewman, Anthony, personal communication with Dean Farwood, May 22, 2010.

- ^Klein, Howard, A Harpsichordist Dazzles in Debut, The New York Times, February 16, 1967.

- ^Newman, Anthony, personal communication with Dean Farwood, June 6, 2010

- ^'Hip Harpsichordist', Time, August 28, 1972, p. 37.

- ^Newman, Anthony, personal communication with Dean Farwood, June 13, 2010.

- ^Cummings, Robert, Anthony Newman Biography

- ^Newman, Anthony, Anthony Newman on Composing

- ^Newman, Anthony, Anthony Newman on Harmony

- ^[1]

- ^Newman, Anthony, Bach and the Baroque, 2nd ed., 1995, pp. 2-3, Pendragon Press, Hillsdale.

- ^Henahan, Donal, 'Anthony Newman's Extraordinary Musical Gifts', The New York Times, August 17, 1972.

- ^ abDavis, Peter G., 'Newman's Bach', The New York Times, June 20, 1979.

- ^Newman, Anthony, 'Inequality: A New Point of View', Musical Quarterly,1992, 76 (2): 169-183.

- ^Neumann, Frederick, 'Letter', Musical Quarterly, 1992, 76 (2): 169-183.

- ^Neumann, Frederick, New Essays on Performance Practice, p. 235, 1989, University of Rochester Press, Rochester.

- ^Neumann, Frederick, New Essays on Performance Practice, pp. 237-239, 1989, University of Rochester Press, Rochester.

- ^Hugues, Allen, 'Bach and all that Razzel-Dazzel', The New York Times, December 7, 1969.

- ^Davis, Peter G., 'Bach Works Are Played By Newman', The New York Times, November 29, 1976

- ^Ericson, Raymond, 'Newman Is Back With Bach', The New York Times, November 26, 1976.

- ^Early Music Revival

External links[edit]

- [2] Anthony Newman, musician

- [3] Anthony Newman: The High Priest of Bach is Still Controversial

- [4] Biography

- [5] Interview

- [6] Biography

- [7] A Newman For All Seasons

- [8] Newman At Large

- Interview with Anthony Newman by Bruce Duffie, October 20, 1989

- At Peace with a Certain Level of Renown 2014

Our editors will review what you’ve submitted and determine whether to revise the article.

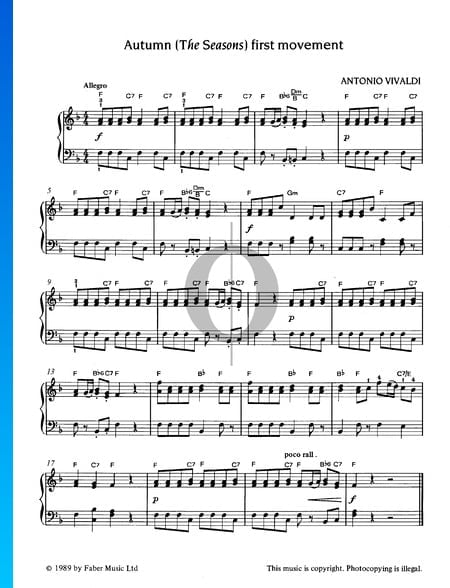

Join Britannica's Publishing Partner Program and our community of experts to gain a global audience for your work!Antonio Vivaldi, in full Antonio Lucio Vivaldi, (born March 4, 1678, Venice, Republic of Venice [Italy]—died July 28, 1741, Vienna, Austria), Italian composer and violinist who left a decisive mark on the form of the concerto and the style of late Baroque instrumental music.

Antonio Vivaldi Compositions

Life

Vivaldi’s main teacher was probably his father, Giovanni Battista, who in 1685 was admitted as a violinist to the orchestra of the San Marco Basilica in Venice. Antonio, the eldest child, trained for the priesthood and was ordained in 1703. His distinctive reddish hair would later earn him the soubriquetIl Prete Rosso (“The Red Priest”). He made his first known public appearance playing alongside his father in the basilica as a “supernumerary” violinist in 1696. He became an excellent violinist, and in 1703 he was appointed violin master at the Ospedale della Pietà, a home for foundlings. The Pietà specialized in the musical training of its female wards, and those with musical aptitude were assigned to its excellent choir and orchestra, whose much-praised performances assisted the institution’s quest for donations and legacies. Vivaldi had dealings with the Pietà for most of his career: as violin master (1703–09; 1711–15), director of instrumental music (1716–17; 1735–38), and paid external supplier of compositions (1723–29; 1739–40).

Soon after his ordination as a priest, Vivaldi gave up celebrating mass because of a chronic ailment that is believed to have been bronchial asthma. Despite this circumstance, he took his status as a secular priest seriously and even earned the reputation of a religious bigot.

Vivaldi’s earliest musical compositions date from his first years at the Pietà. Printed collections of his trio sonatas and violin sonatas respectively appeared in 1705 and 1709, and in 1711 his first and most influential set of concerti for violin and string orchestra (Opus 3, L’estro armonico) was published by the Amsterdam music-publishing firm of Estienne Roger. In the years up to 1719, Roger published three more collections of his concerti (opuses 4, 6, and 7) and one collection of sonatas (Opus 5).

Vivaldi made his debut as a composer of sacred vocal music in 1713, when the Pietà’s choirmaster left his post and the institution had to turn to Vivaldi and other composers for new compositions. He achieved great success with his sacred vocal music, for which he later received commissions from other institutions. Another new field of endeavour for him opened in 1713 when his first opera, Ottone in villa, was produced in Vicenza. Returning to Venice, Vivaldi immediately plunged into operatic activity in the twin roles of composer and impresario. From 1718 to 1720 he worked in Mantua as director of secular music for that city’s governor, Prince Philip of Hesse-Darmstadt. This was the only full-time post Vivaldi ever held; he seems to have preferred life as a freelance composer for the flexibility and entrepreneurial opportunities it offered. Vivaldi’s major compositions in Mantua were operas, though he also composed cantatas and instrumental works.

The 1720s were the zenith of Vivaldi’s career. Based once more in Venice, but frequently traveling elsewhere, he supplied instrumental music to patrons and customers throughout Europe. Between 1725 and 1729 he entrusted five new collections of concerti (opuses 8–12) to Roger’s publisher successor, Michel-Charles Le Cène. After 1729 Vivaldi stopped publishing his works, finding it more profitable to sell them in manuscript to individual purchasers. During this decade he also received numerous commissions for operas and resumed his activity as an impresario in Venice and other Italian cities.

In 1726 the contralto Anna Girò sang for the first time in a Vivaldi opera. Born in Mantua about 1711, she had gone to Venice to further her career as a singer. Her voice was not strong, but she was attractive and acted well. She became part of Vivaldi’s entourage and the indispensable prima donna of his subsequent operas, causing gossip to circulate that she was Vivaldi’s mistress. After Vivaldi’s death she continued to perform successfully in opera until quitting the stage in 1748 to marry a nobleman.

In the 1730s Vivaldi’s career gradually declined. The French traveler Charles de Brosses reported in 1739 with regret that his music was no longer fashionable. Vivaldi’s impresarial forays became increasingly marked by failure. In 1740 he traveled to Vienna, but he fell ill and did not live to attend the production there of his opera L’oracolo in Messenia in 1742. The simplicity of his funeral on July 28, 1741, suggests that he died in considerable poverty.

After Vivaldi’s death, his huge collection of musical manuscripts, consisting mainly of autograph scores of his own works, was bound into 27 large volumes. These were acquired first by the Venetian bibliophile Jacopo Soranzo and later by Count Giacomo Durazzo, Christoph Willibald Gluck’s patron. Rediscovered in the 1920s, these manuscripts today form part of the Foà and Giordano collections of the National Library in Turin.

Antonio Vivaldi

- born

- March 4, 1678

Venice, Italy

- died

- July 28, 1741 (aged 63)

Vienna, Austria

- notable works

- movement / style